Discover How Beneficial Soil Microbes Boost Plant Growth

Discover How Beneficial Soil Microbes Boost Plant Growth

Have you ever followed all the gardening rules, yet your plants still struggle? You provide water, sunlight, and maybe some fertilizer. Still, the soil feels lifeless, either cracking and dry or dense and waterlogged.

The problem might not be what you are adding, but what you are missing. Beneath your feet is a bustling, microscopic city full of life. This guide is about the unseen workers that can transform your soil, the vast community of beneficial soil microbes.

You will learn what these tiny organisms are and why they are so important. We will explore how to bring them back to your garden. Understanding the role of beneficial soil microbes can completely change how you grow everything.

Table of Contents:

- What Are Beneficial Soil Microbes?

- The Key Players: Getting to Know the Microbes

- Why Does This Tiny World Matter So Much?

- How to Cultivate Your Own Beneficial Soil Microbes

- Practices That Harm Soil Life

- Seeing is Believing: A Look Under the Microscope

- Frequently Asked Questions About Soil Microbes

- Conclusion

What Are Beneficial Soil Microbes?

When you hear the word microbes, you might think of germs that cause illness. But most microbes on our planet are not harmful. In fact, life as we know it could not exist without them.

Beneficial soil microbes are the tiny, living organisms that make soil alive. A single teaspoon of healthy soil can contain billions of these organisms. This community includes bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and nematodes, all contributing to a vibrant soil biology.

Together, they form what scientists, like the pioneering Dr. Elaine Ingham, call the Soil Food Web. Think of it as a complex food chain, all happening within the dirt. These creatures work together to break down organic matter, build soil structure, and feed your plants, creating a healthy soil ecosystem.

The Key Players: Getting to Know the Microbes

This underground community has several key groups, and each plays a different but essential part. Let's meet the main players that are foundational to soil health. Understanding their jobs helps you manage your soil more effectively.

Bacteria: The First Responders

Bacteria are usually the first to arrive at any decomposition party. They are the smallest and most numerous microbes in the soil. They are the foundation of the soil food web.

These tiny powerhouses are expert decomposers that break down simple organic materials, releasing locked-up nutrients. Some bacteria, like Rhizobia, form partnerships with legumes to pull nitrogen from the air and make it available to the plant. Others are excellent at solubilizing phosphorus, making another critical nutrient accessible.

Bacteria also produce a sticky 'glue' that binds small soil particles together, forming microaggregates. These microaggregates are the first step to building good soil structure. They also serve as a primary food source for larger microbes in the soil.

Fungi: The Underground Engineers

Fungi are another group of master decomposers, but they specialize in tougher materials. They break down complex, carbon-rich plant debris like wood and stalks. You may see them as mushrooms, but most of their work happens underground through vast networks of thread-like hyphae.

These fungal hyphae act like a web, weaving through the soil. They bind the bacterial microaggregates together into larger macroaggregates. This process creates the channels and pores needed for air and water, preventing soil compaction and improving drainage.

Some researchers have explored how fungi create a subterranean communication network. Italian botanist Stefano Mancuso writes about how plants can use these fungal networks. Through them, plants can exchange nutrients and warning signals, creating a connected plant community.

Mycorrhizal Fungi: The Plant's Best Friend

A particularly important group is mycorrhizal fungi, which form a direct symbiotic relationship with plant roots. The fungus extends the plant's root system far into the soil. This massively increases the plant's ability to access water and nutrients like phosphorus and zinc.

In return, the plant provides the fungus with sugars produced during photosynthesis. This partnership benefits more than 90% of all land plants. There are two main types: endomycorrhizae, which penetrate root cells, and ectomycorrhizae, which form a sheath around them.

Cultivating these fungi is a cornerstone of regenerative agriculture. They improve plant health and reduce the need for fertilizers. Their hyphae also produce glomalin, a sticky protein that is a major component in building stable soil structure.

Protozoa: The Nutrient Recyclers

Protozoa are single-celled organisms that are larger than bacteria. Their primary job is to eat bacteria. This might sound simple, but it is critical for plant health and nutrient availability.

Bacteria contain a lot of nutrients, like nitrogen, but it's locked in their bodies in a form plants cannot use. When protozoa consume bacteria, they excrete the excess nutrients as waste. This process converts the nutrients into a simple, plant-available form right at the root zone.

Beneficial protozoa like amoebas and flagellates are signs of healthy, aerobic soil. Other types, like ciliates, often indicate that the soil is low on oxygen. Observing them in a microscope sample can tell a soil consultant a lot about the soil's condition.

Nematodes: Not All Are Bad Guys.

Nematodes often have a bad reputation among gardeners. Many people only know about root-feeding nematodes that damage plants. But most nematodes in your soil are beneficial.

There are several types of helpful nematodes that perform vital functions. Bacterial-feeding nematodes eat bacteria, and fungal-feeding nematodes eat fungi. Just like protozoa, they are crucial for nutrient cycling by releasing plant-available nutrients.

There are also predatory nematodes that help control pest populations, including the destructive root-feeding types. A diverse and balanced soil food web keeps the damaging organisms in check naturally. Having a healthy population of beneficial nematodes is a sign of a complex and stable soil ecosystem.

Why Does This Tiny World Matter So Much?

Understanding these microbes is one thing, but why should you care? A thriving soil food web provides real, tangible benefits to your garden, lawn, or farm. It is the foundation of practices like regenerative agriculture.

A living soil means your plants get what they need to grow strong and healthy, naturally. This reduces your workload and your dependence on chemical products. You end up with better soil, healthier plants, and more nutritious food.

By focusing on the life in your soil, you start working with nature instead of against it. Let's look at the specific jobs these microbes do for you.

Superior Nutrient Cycling

Healthy soil is full of nutrients, but they are often locked up in rocks, clay, and organic matter. Plants cannot access them in this form. You need microbes to unlock them and make them available.

Beneficial microbes are like tiny chefs, preparing a meal for your plants. They digest these complex materials and release simple, soluble nutrients that plant roots can easily absorb. A healthy soil ecosystem constantly feeds your plants, which can reduce or eliminate the need for synthetic fertilizers.

Improved Soil Structure

Do you struggle with soil that's either hard as a rock or turns to mud when it rains? This is a problem of poor structure. Microbes are the solution.

The glues from bacteria and the webs of fungi bind soil particles together into aggregates. This creates a crumbly, spongy texture full of air pockets. This structure allows water to soak in and be stored, preventing runoff and protecting plants from drought stress.

Good structure also lets roots grow deeper and more easily, accessing more resources. If your yard develops deep cracks in the summer, it's a clear sign that your soil lacks microbial life. Improving soil biology is the best way to fix these physical problems.

Natural Pest and Disease Suppression

In a diverse microbial ecosystem, there is a lot of competition for food and space. This intense competition makes it hard for plant pathogens to establish themselves. The beneficial organisms simply crowd out the harmful ones through a process called competitive exclusion.

Additionally, some beneficial microbes are predatory, actively consuming pathogens. Certain fungi can trap and consume harmful nematodes. A healthy soil is a protected soil.

On top of that, healthy plants with great nutrition have stronger immune systems. They are much better at fending off pests and diseases on their own. Fostering a healthy soil food web creates a system that naturally protects your plants.

How to Cultivate Your Own Beneficial Soil Microbes

Now for the best part: you can cultivate these microbes yourself. You do not have to rely on expensive bottled products. By creating the right environment, you can encourage them to thrive.

Permaculture principles guide us to work with what we have. That means gathering local organisms and feeding them well. Here is how you can start building your own microbial army.

Start with Good Compost

Compost is the best way to introduce a diverse community of microbes to your soil. But not all compost is created equal. A passive, cold pile of leaves will not have the same life as a carefully managed thermophilic compost pile.

Thermophilic composting involves reaching high temperatures (131-160°F) to kill pathogens and weed seeds. This process also cultivates a rich diversity of beneficial organisms. This 'biologically complete' compost is an inoculum that seeds your soil with the life it needs.

Feed Them What They Like

Different microbes have different diets, just like people. To get a good balance of organisms, you need to provide a balanced diet in your compost pile. We classify ingredients based on their carbon-to-nitrogen ratio.

This sounds technical, but it is simple in practice. Green, fresh materials are high in nitrogen and feed bacteria. Brown, dry, and woody materials are high in carbon and feed fungi.

| Material Type | Examples | Primary Feeder |

|---|---|---|

| High Nitrogen | Fresh manure, alfalfa, food scraps. | Bacteria |

| Green Materials | Green leaves, grass clippings. | Bacteria |

| Brown Materials | Dry leaves, straw, shredded paper. | Fungi |

| Woody Materials | Wood chips, twigs, sawdust. | Fungi |

By using a mix of these materials, you grow a diverse population of both bacteria and fungi. A good starting point for a compost pile is a carbon-to-nitrogen ratio of about 25:1 to 30:1. This diversity is what makes the soil ecosystem resilient.

Keep Your Soil Covered

Bare soil is a sign of a broken system, as nature always tries to cover the ground. You should, too. Applying a layer of mulch protects the soil from sun, wind, and rain.

Mulch, like wood chips or straw, helps retain moisture and keeps soil temperatures stable. Most importantly, it serves as a slow-release food source for your soil microbes, especially fungi. Over time, this organic matter will be incorporated into the soil by its inhabitants.

You can also use cover crops, which are plants grown specifically to protect and improve the soil. Their living roots create channels in the soil and release compounds that feed microbes. When you terminate the cover crops, their biomass becomes food for the entire soil food web.

Practices That Harm Soil Life

Just as important as adding good things is avoiding practices that destroy the soil ecosystem. Many common gardening and farming methods can wipe out beneficial microbes. Protecting your existing soil biology is the first step.

Physical Disturbance: Tillage

Tilling or plowing the soil is like an earthquake, hurricane, and fire combined for microbes. It destroys the fungal hyphae networks that are essential for good soil structure. It also exposes protected organic matter to rapid decomposition, burning through your soil's carbon reserves.

This physical destruction breaks apart the soil aggregates that microbes build. The result is compacted soil that is prone to erosion. Reducing or eliminating tillage is one of the most effective ways to support soil life.

Chemical Inputs: Fertilizers & Pesticides

Synthetic nitrogen fertilizers can feed plants directly, but they often do so at the expense of microbes. They can harm or inhibit nitrogen-fixing bacteria and mycorrhizal fungi. Plants may reduce their association with microbes if they get easy access to synthetic nutrients.

Pesticides, herbicides, and fungicides can be even more destructive. These chemicals are often non-selective, killing beneficial insects, fungi, and other organisms along with the target pest. This disrupts the soil food web and can allow pathogens to rebound quickly without natural predators to keep them in check.

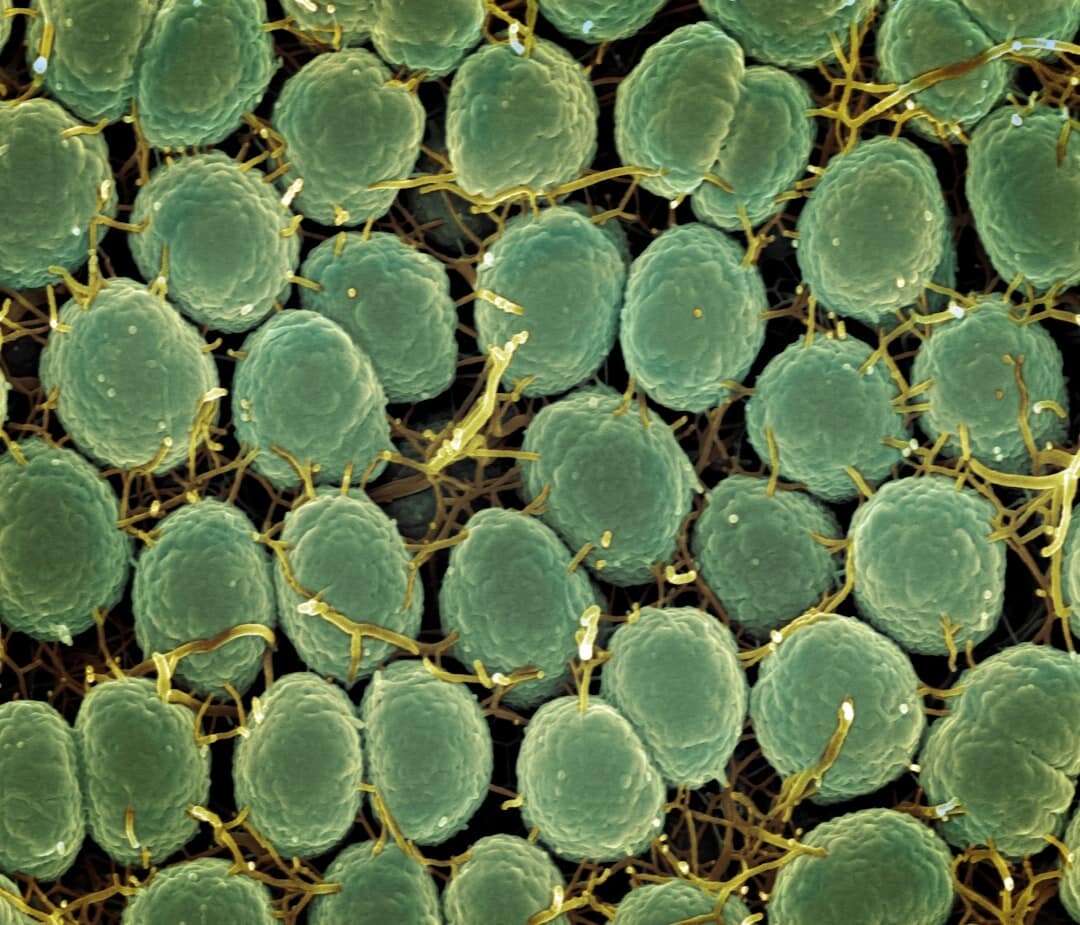

Seeing is Believing: A Look Under the Microscope

As a Soil Food Web Lab Technician, I see this hidden world every day. Looking at a drop of soil or compost tea through a microscope is fascinating. You see a jungle of activity, not just inert particles.

I can see wiggly nematodes hunting for bacteria and watch amoebas ooze across particles of sand. I can identify the long, beautiful strands of beneficial fungi, which are a sign of a healthy, fungal-dominated system. This visual confirmation is a powerful learning tool.

This is not just for observation, though. A microscopic analysis tells me exactly what is happening in a client's soil. I can measure microbial populations and determine the fungal-to-bacterial (F:B) ratio, which helps us understand what plants will grow best and what the soil needs to improve.

Frequently Asked Questions About Soil Microbes

Can I just buy beneficial microbes?

Yes, many products containing microbes are available, from mycorrhizal inoculants to compost teas. While they can be helpful for kickstarting a system, they are not a long-term solution on their own. The microbes need the right habitat and food to survive and multiply.

It is generally more sustainable and effective to create the right conditions with compost and mulch. This allows native and introduced microbes to establish a permanent, self-sustaining population. Focusing on the habitat is always the primary goal.

How long does it take to improve my soil's microbial life?

The time it takes depends on your starting point and your methods. You can see initial changes within a single season. Applying good compost and mulch can immediately boost microbial activity.

However, building deep, resilient soil structure and a complex food web is a longer process. It can take several years of consistent, positive practices. The key is patience and providing a steady food source for your soil life.

Is tillage really that bad for soil?

Yes, from a soil biology perspective, tillage is highly destructive. It shatters the fungal networks that are critical for soil aggregation and water retention. It also leads to a loss of soil organic matter.

While some situations may call for initial, minimal tillage to break up severe compaction, the long-term goal should always be to reduce or eliminate it. No-till or low-till methods combined with cover crops are far better for long-term soil health. This protects the delicate home you are building for your microbes.

Conclusion

Your soil is not just an inert medium for holding up plants. It is a living, breathing ecosystem that forms the foundation of health for your garden or farm. Shifting your focus from feeding the plant to feeding the soil changes everything.

By learning to work with nature's systems, you can build resilient soil. This soil cycles nutrients, stores water, and fights off disease on its own. You can grow healthier plants and more nutritious food with less work and fewer chemical inputs.

It all starts with fostering the community of beneficial soil microbes. They are waiting to get to work right under your feet. All you have to do is create the right conditions for them to thrive.